|

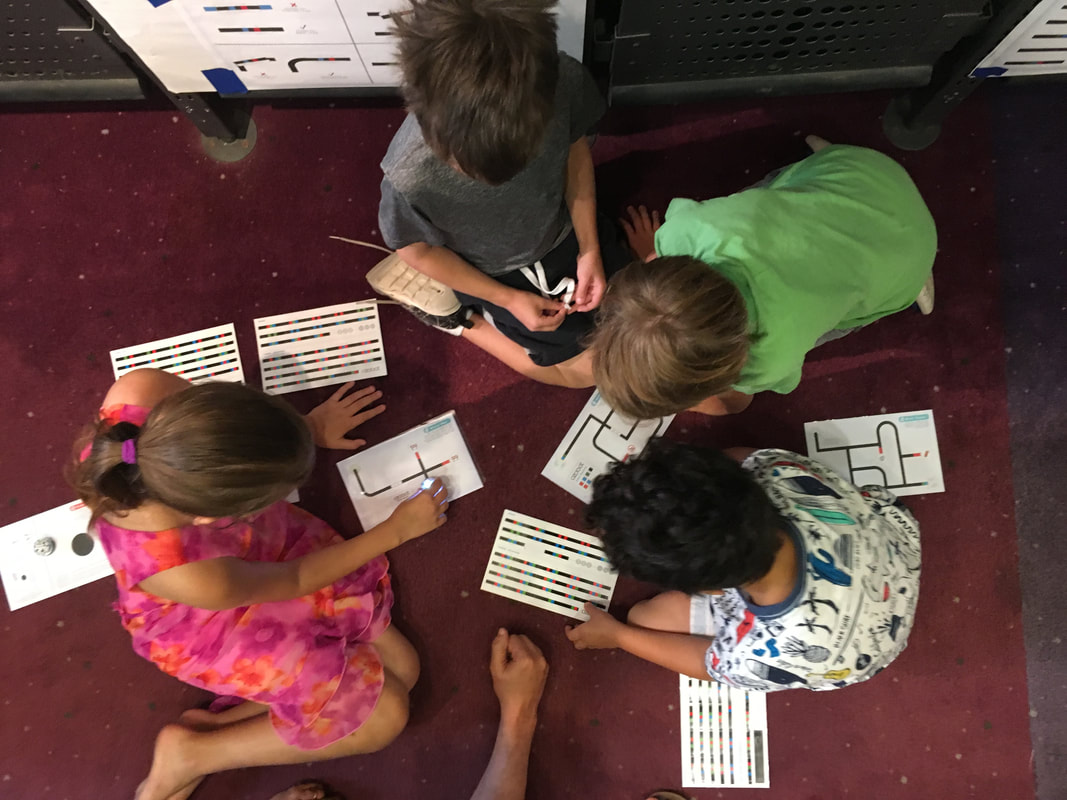

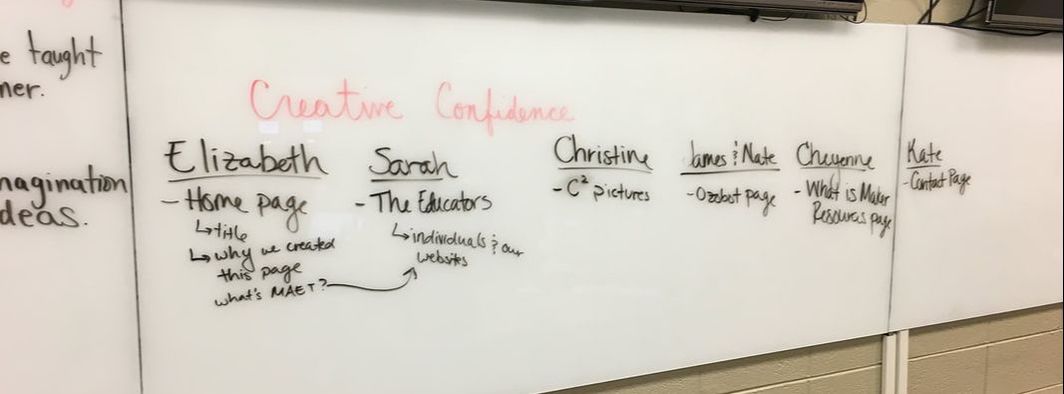

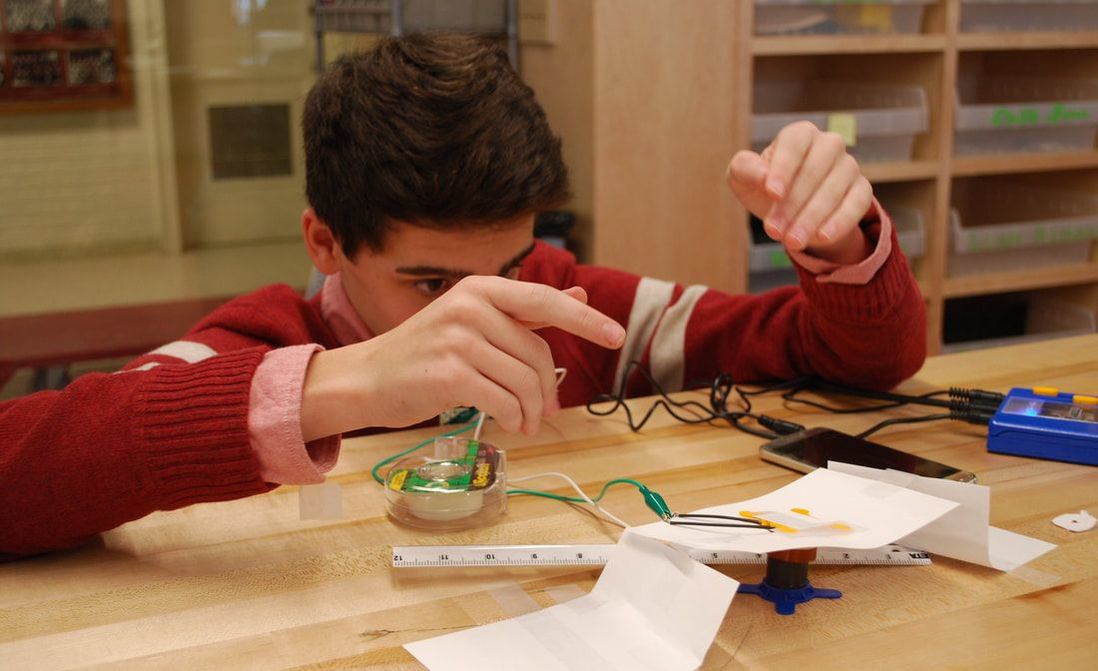

Our MAET first-year cohort was tasked with building a website (maetymakers2018.weebly.com/), meant to be a resource for educators that are looking for an introduction to the Maker movement with some practical examples of how they could implement activities in their classroom. The goals of the project included the exploration of the Maker movement and Maker-style projects, collaboration on website design and implementation, and the design of an activity and resource page for fellow teachers. The entire cohort was tasked with collaborating on general pages on the site, and we were split into small groups in order to design a specific activity and corresponding page to explain it. My partner and my focus was to create a Maker activity involving Ozobots: small line-following robots that are capable of “reading” colors and reacting to instructions, communicated as particular sequences of colors. We selected this educational technology from a variety of available tools because of its low barrier to entry, immediate engagement (“cool” factor), and the potential for low-overhead creativity and exploration. The Ozobot will follow a line drawn by the included markers, or line maps on included cards. The cards are designed in a sequence that scaffolds skills and knowledge as students work their way through. Color codes can be drawn with markers, and students can also use included color code decals that work in coordination with the included cards, to tell the Ozobots to turn, change speeds, set timers, or move in special ways, such as “Nitro Boost” or “Tornado.” We were interested in designing a teacher-guided activity that would introduce a group of elementary students to the basic functionality of Ozobots, while trying to balance instructive time and creative or problem-solving time. We had an opportunity to prototype our activity, and test it out on a group of mixed-age STEM summer campers at TinkrLab in Lansing, MI (“Smart Toys for Smart Kids”). Without a full understanding of the format of the activity, we tried to create a flexible, primarily self-guided activity. We gained valuable insight into the Ozobot technology and the way that young students intuitively use it. We were surprised by the youngest students’ lack of fine motor skills, which hindered their ability to draw accurate codes. The format of the activity time was fairly casual, and the students had some experience with the technology already, which hindered our ability to gauge novice student reactions to our activity. Nonetheless, we did observe that the students were interested and engaged with the tool, and most excited about the opportunities to solve the “Brain-Teaser” problems or to design their own maps and paths for the Ozobot to follow. After digesting the experience at TinkrLab, we shifted our focus to developing the website. Collaboratively designing and building the site was a challenge. Our preliminary planning took place in a shared Google Doc, in which we were able to outline our page and maintain a running list of outstanding questions. Initial planning went smoothly, but we ran into some bumps in the road when we began to actually build the site. Working with educators who are used to being the primary voice in the front of a classroom can lead to a “too many cooks in the kitchen” situation very quickly. Trying to build the page “live” with input from each of us was ineffective, so we quickly distributed the primary building tasks between the members in order to separate the work. We depended on the built-in themes and styles of the website building tool (Weebly.com) to create a cohesive look and feel for the site. Progress improved when we were able to delegate tasks. My partner and I focused on planning the content and layout of our page in a Google Doc before transferring our ideas to Weebly. I’m heavily involved in the Maker world in my day-to-day work at my home school, and believe strongly in the Maker paradigm as a way to deeply engage students with 21st century content while also developing softer skills, such as creative confidence, collaboration, critical thinking, and problem-solving. I am a Maker at heart, and find tremendous satisfaction in creating physical artifacts that are both beautiful and functional, and in sharing my passion with my students. It is easy to be proud of an accomplishment that not only exists in a student’s mind, but can stand on its own as evidence of creativity, hard work, discovery, learning, and problem solving. Punya Mishra & The Deep-Play Research Group (2012) have explored the idea of creativity, and invented the idea of, “(in)disciplined creative work, (a) meaning that creative work always happens in a discipline or context; while understanding that (b) at the same time, it is indisciplined, cutting across the boundaries of discipline to emphasize divergent thinking and creativity” (p. 15). Some students feel as though they are creative in once discipline but not in others, which is easy to agree with based on their talents and experiences. I believe, however, that creative confidence is transferrable across disciplines, and is fostered by Maker-style projects.

In a best-case scenario, Maker projects are authentic, relevant to the student’s context, and naturally lead the students to the important questions of the educator-chosen topic or concept. Instructors can gently guide, support, and encourage the students as they work to find their own answers and develop their project. As with any technology, we need to be careful not to assume that the Maker tool alone is capable of achieving our educational objectives. We must remain focused on the content and pedagogy in order to build successful lessons. I struggled to find authenticity in this activity, to understand the context of the potential learners, and to properly target the content, since we didn’t have a clear target audience. Ozobots do hold promise as an engaging introduction to programming, but it’s not truly a robotics platform, nor is it a very strong “Maker” tool. There are opportunities for creative play and exploration, but it doesn’t hit the Maker “sweet spot.” Maker tools and materials don’t need to be high-tech or expensive, they simply need to provide opportunities for students to design, build, test, revise, showcase and share their creations. Carefully planned content, pedagogy, and thoughtful educator guidance are more important to a successful Maker project than the tools. Resources: Mishra, P., & The Deep-Play Research Group (2012). Rethinking technology and creativity in the 21st century: Crayons are the future. TechTrends, 56(5), 13-16.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorNate is the Director of Technology at the Roxbury Latin School Archives

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed