|

Failure is good!! Failure is great! Let’s fail all the time! This seems to be the message in progressive education in the past few years. Warren Berger discusses the rise of this concept in his book, A More Beautiful Question: The power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas. He notes how the idea shows up in a commencement speech by Oprah Winfrey in 2013, and “has been a popular credo in Silicon Valley.” (2014) It’s easy to find disciples of this trendy idea. A quick Google search yields articles such as Why Failure Is Good for Success (success.com), Lessons on Success: 3 Reasons Why Failing is Good (monster.com), Failure Is Good (psychologytoday.com), and Why Failure Is Good For You (Even If It Doesn't Feel Good) (bustle.com).

I understand the sentiment: let’s destigmatize failure, and see it as a learning opportunity instead of a cause for distress. Learn from your mistakes. Build on your failures. Generally, I don’t disagree. Particularly when targeted at adults who have experienced and felt real failure, this concept is valuable and powerful. What I worry about is bringing this mantra to our young students. Failure still has meaning, as a word and as a concept. Failure does NOT achieve the stated goal, and can have serious repercussions. Daniel Altman began to question this “Failure Fetish” in his article on the website Big Think (2013). He defends the value of careful consideration and thought instead of simply aiming to “fail fast.” My concern is related, but particular to the world of education. Creating an educational world where failure is spun as a positive comes with a few notable challenges. My theory is this: the mantra of “failure is good” diminishes the value and power of failure. The “nounification” of the word fail (“That’s a fail.”), and the exponential growth of phrases such as “epic fail” indicates that the idea of failure is being employed at a micro-level in the lives of our students. Any slight misstep suddenly becomes a “fail.” Failure, by nature and definition is a terminal concept. A failure comes at the end of a process, when the final efforts fall short of the goals or expectations. Creating a world of micro-failures creates opportunities for students to a) tear each other down in a continual stream of microaggressions throughout their day, and b) diminish the value and meaning of the concept itself. It also seems to be related to the era of the short-attention, immediate gratification, 140-characters or less way of navigating our world. If an “epic fail” can happen on a first try of a meaningless task, how seriously are they taking the concept of failure? We can learn from our failures, but if students are seeing themselves “failing” hundreds of times every day, how many of those micro-failures are they actually likely to try to improve on or learn from? Fail. Move on. Next thing. My suggestion is that we move away from the “failure is good” mantra in education. Instead, we reframe what we’re currently calling failure as simply a first try, an iteration, a draft, depending on the context. In the vast majority of cases, what students are referring to as “a fail” is not actually a failure. Nobody has failed yet, because there’s no reason that the process should be terminal yet. It’s simply a first try! Rather than pointing to a sub-par first iteration as a “failure” and talking about how much we can learn from it, we should assume a second iteration and ask instead, “How are you planning to change or improve it for your next iteration?” If students don’t feel like their failing, we have no need to reframe this idea of failure as a good thing. In the much less common cases when there was a legitimate failure, we can talk about how to move on and grow. Let’s not make everything a failure. Resources: Berger, W. (2014). A More Beautiful Question: The power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas. New York: Bloomsbury. Altman, D. (2013, June 11). The Failure Fetish. Retrieved August 16, 2018, from https://bigthink.com/econ201/the-failure-fetish

0 Comments

People with “all the answers” must not get asked good questions very often. Good questions cause you to pause, digest, and respond with more questions rather than immediate answers.

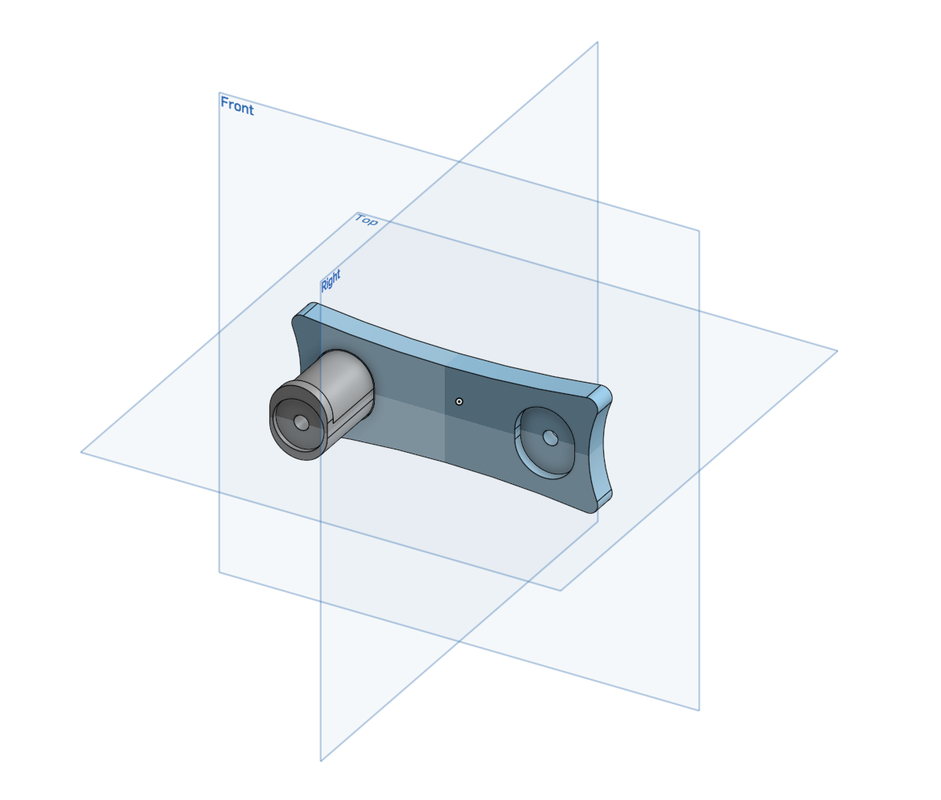

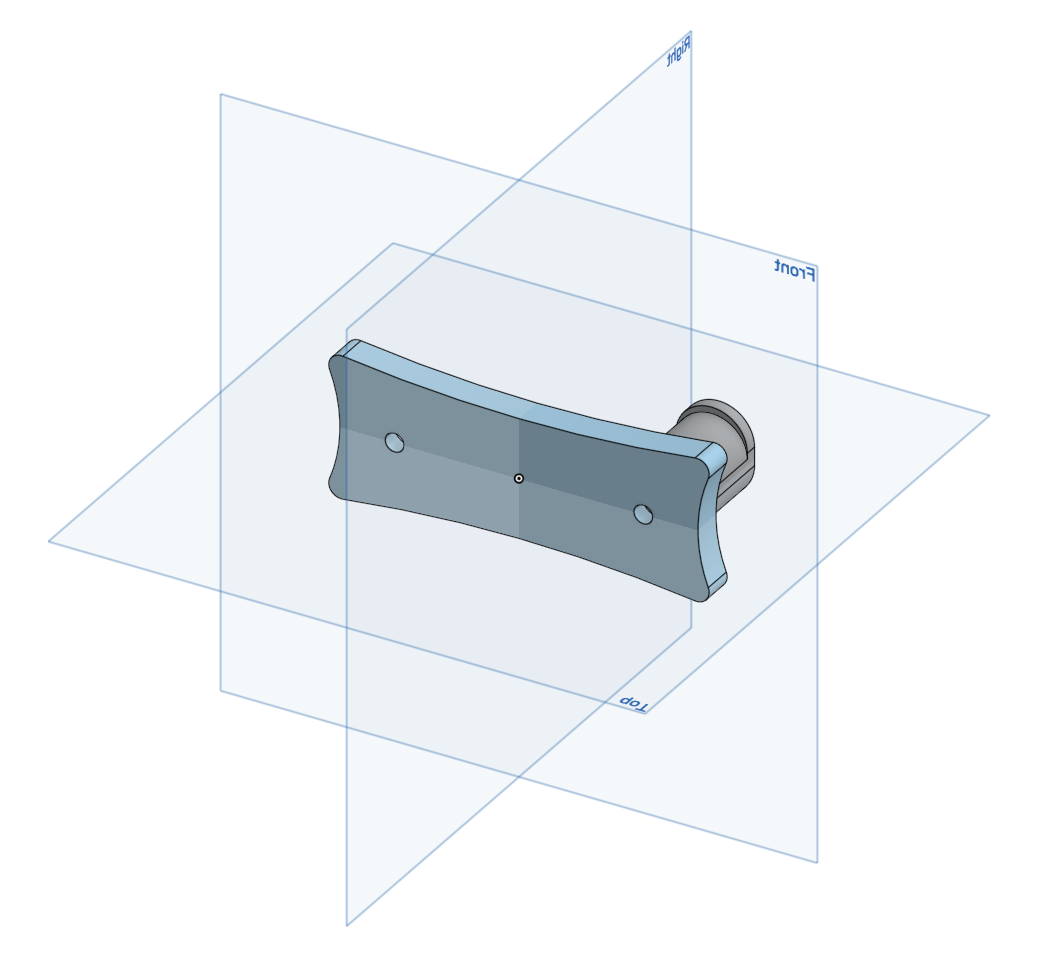

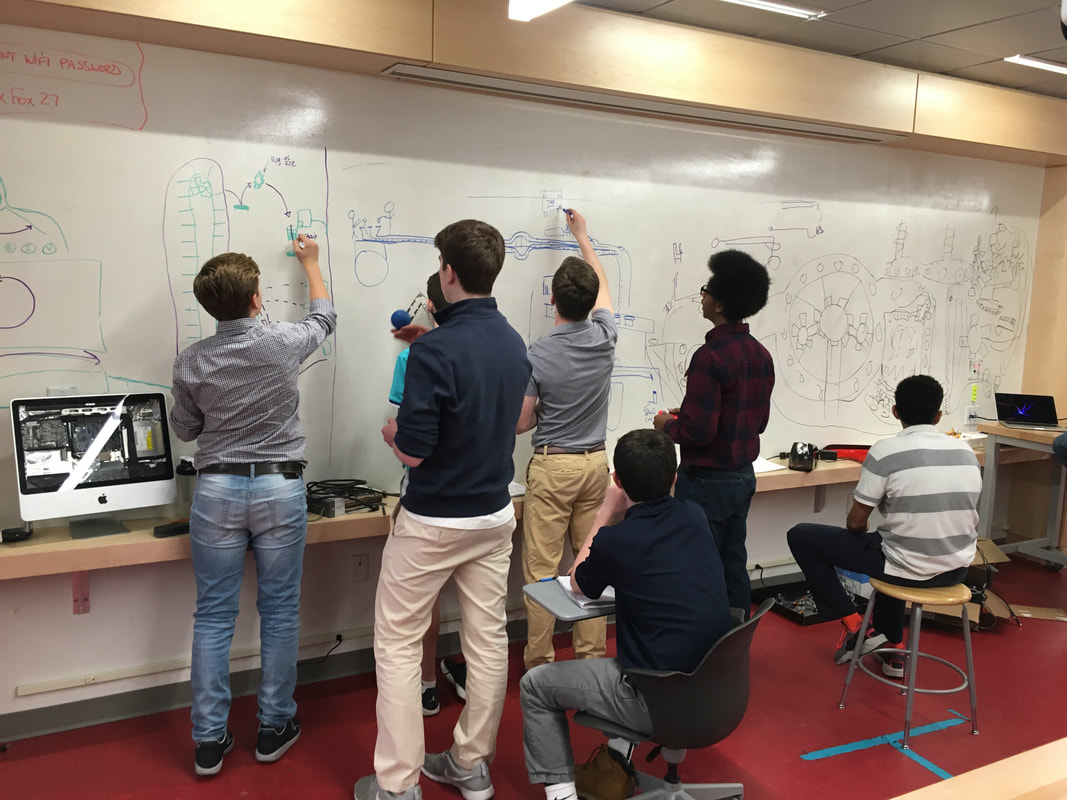

When presented with a problem worth solving, a series of intentional question-asking steps can be helpful in guiding your thought. Particularly, Warren Berger suggests a “why,” “what if,” and “how” method (Berger, 2014). Examining a problem first with “why” can help to create a deeper understanding of the problem. Why are things the way they are? Once you’ve clarified the actual problem, “what if” questions can help to determine what some possible solutions might be. What if things were this way instead? In casual thought, most of us stop there. We identify some possible solutions and then move on to our next problem, because it seems daunting, we don’t have the time, or we’re scared of failure (Kelley & Kelley, 2013). The people that are actually out there solving the world’s problems are the ones willing to go beyond the “what if,” and start to meaningfully engage with the “how.” How could we actually do this? In a school, problems arise all the time that might have relatively simple solutions, but issues of time, tradition, and governance often discourage faculty and staff from getting far beyond the “why.” We can all identify a chronic “why-er” or two in our workplaces, probably more often referred to as a whiner or complainer. Perhaps you’ve even experienced an occasion when a “what if” is posed to a “why-er,” and they seem to check out - uninterested in actually pursuing a solution to their “why.” Particularly in schools, where there are plenty of problems to solve, we need to stop coalescing around the whys, and move toward the what ifs and hows. I want to encourage those of you who are engaged by the “what if” and “how” questions to put aside concerns about whether you might be “allowed” to pursue solutions to your given problems, and to adopt a rebel spirit. Rebels typically aren’t “up to no good” - rather - they’re simply pursuing solutions that don’t fit inside the box. Often times it’s the rebels that are the innovators and the world-changers. They don’t worry so much about the outside constraints of their role, and the pursue what it is that engages them in the best ways they know how. (NPR, 2018) I’ll present one example of a subtle “rebel” activity that turned out well for me. In my school, we have quarterly report meetings, in which we spend a whole day working our way through each grade, trying to talk about every kid in the school, and spending more time on students that might be having a tough time for one reason or another. While faculty dutifully report to these meetings, and collectively acknowledge that it’s good that we have them, they can be long and somewhat dry, particularly when you don’t actually work with the students being discussed. Some of the “why” questions that came to mind for me were, “Why is it hard to follow along in these meetings?”, “Why is hard to get a sense of who a kid is if we don’t work with them?”, and “Why don’t we use technology to help guide these meetings?” It seemed to me that it was hard to follow along because when you inevitably drifted into an unrelated thought and then came back, there was no visual indicator of who we were discussing. The options were to pretend you knew what was going on, or to bashfully whisper to your neighbor, “Who are we talking about?” It was hard to get a sense of who a kid was because there was no context provided beyond a hard-to-read single-page spreadsheet printout of all the kids in the grade, and all of their grades for the marking period. We didn’t use technology because there wasn’t an obvious tool readily available, and because we had “always done it” this certain way. My “what if” questions were, “What if there were a way to see who we were talking about? What if there was a way to get a little more texture on who they are? What if we could use technology to pull this information together in a meaningful way?” Rather than complaining, or arranging meetings to see if anyone else thought it might be useful, or creating a committee to talk about it, I asked myself, “how?” I taught myself a little bit of JavaScript, HTML, and CSS, found a few useful libraries, learned about our student information system and how to pull data from it, and built a “dashboard” that shows a student’s picture, name, grade, and hometown, shows a list of their athletics and activites, a line chart that shows their grade progress in each class over the year, and a table with their letter grades. I proposed it to the individuals leading each meeting with a prototype, and they were cautiously optimistic and willing to try it. Certain individuals were particularly skeptical, but after the meetings, the feedback was unanimously positive. There were also suggestions about how the dashboard could be further improved. Of course I'm not suggesting that it’s “easy” to learn how to build a custom web dashboard - my background is in computer science, and it was a challenge for me. What I am suggesting is that when you identify a problem, use your background and resources to the best of your ability to get beyond “why,” and get started on “what if” and “how” - regardless of whether you’ve gotten specific permission to do so. Once your “rebellious” act solves a problem, it suddenly becomes an innovation. Resources: Berger, W. (2014). A More Beautiful Question: The power of inquiry to spark breakthrough ideas. New York: Bloomsbury. Kelley, T., & Kelley, D. (2013). Creative confidence: unleashing the creative potential within us all. First edition. New York: Crown Business. NPR. You 2.0: Rebel With A Cause. (2018, July 24). Retrieved August 16, 2018, from https://www.npr.org/templates/transcript/transcript.php?storyId=631524581 As a wrap-up to my first year experience in the Master of Arts in Educational Technology program, I was asked to make something. Anything. As long as it demonstrated my PQ and CQ. While I think the intention was the creation of a digital artifact, I went a slightly different direction. The hanging whiteboard and the 3D printed hanger are the things that I made. My classroom has a large whiteboard in the front of the room, but students most often work at the tables around the room. The whiteboards give them an opportunity to quickly engage with ideas collaboratively, while not introducing more furniture to an already crowded room. This project is meant to speak for itself, so I'll let these images do the talking. I'll also include a link to the OnShape CAD design, in case you're interested in using or remixing the hanger design.

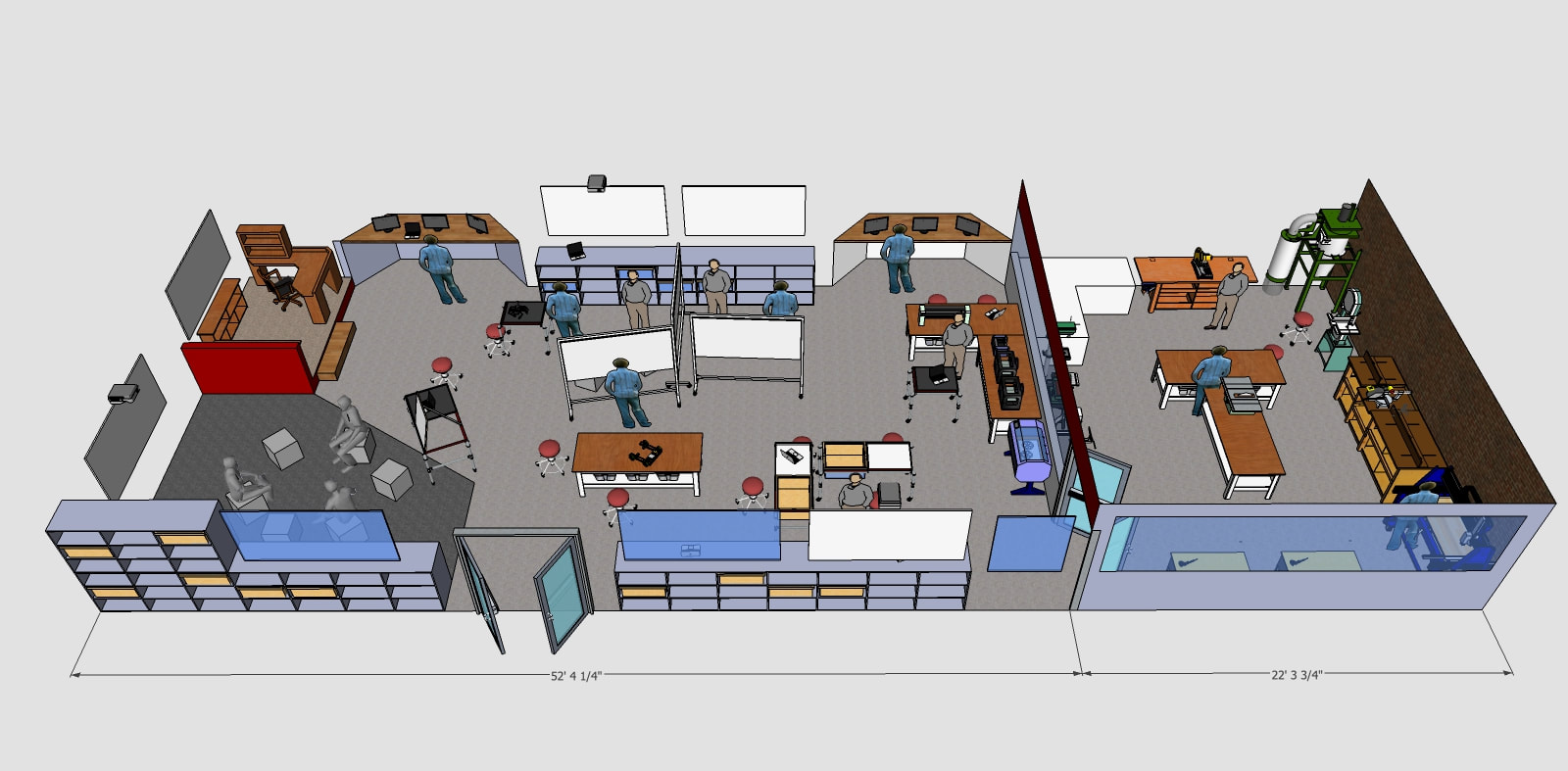

Four years ago, I was fortunate to be a part of major learning space redesign. My school had determined that more intentional STEAM-based educational experiences were needed, and committed to renovating a space on campus to serve as the headquarters for those opportunities. My initial proposals for the space involved several non-negotiables. We needed:

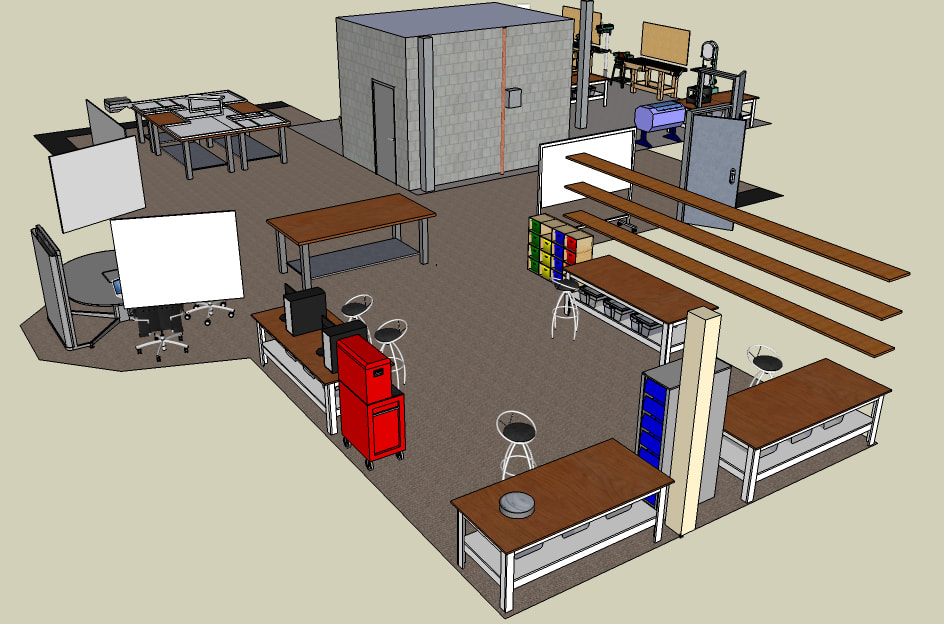

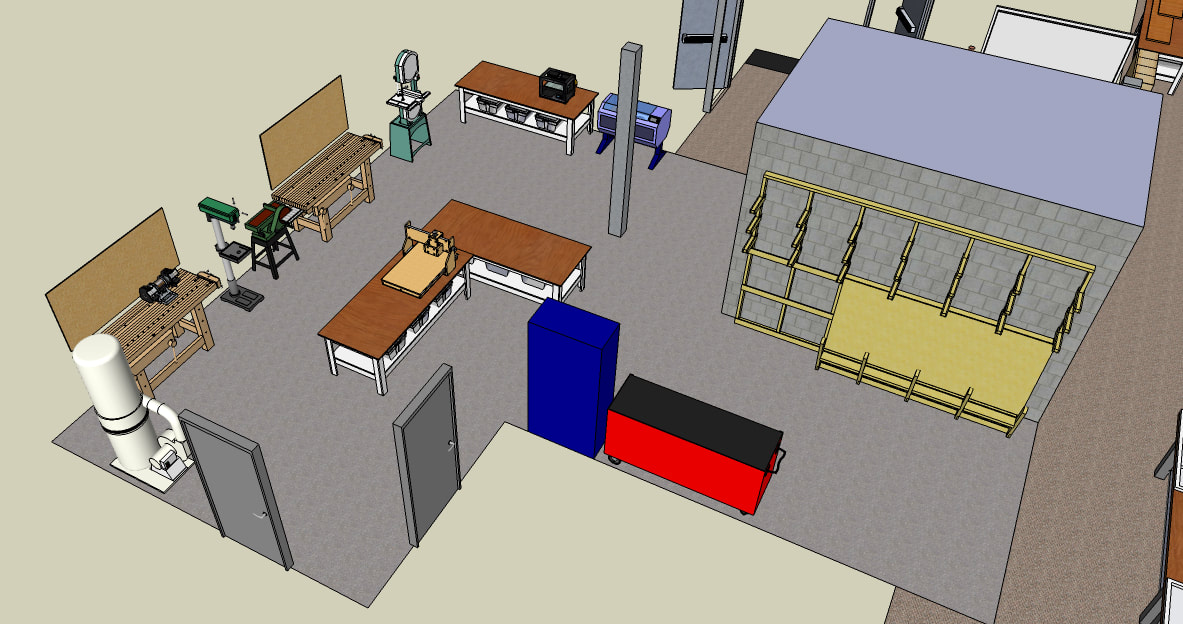

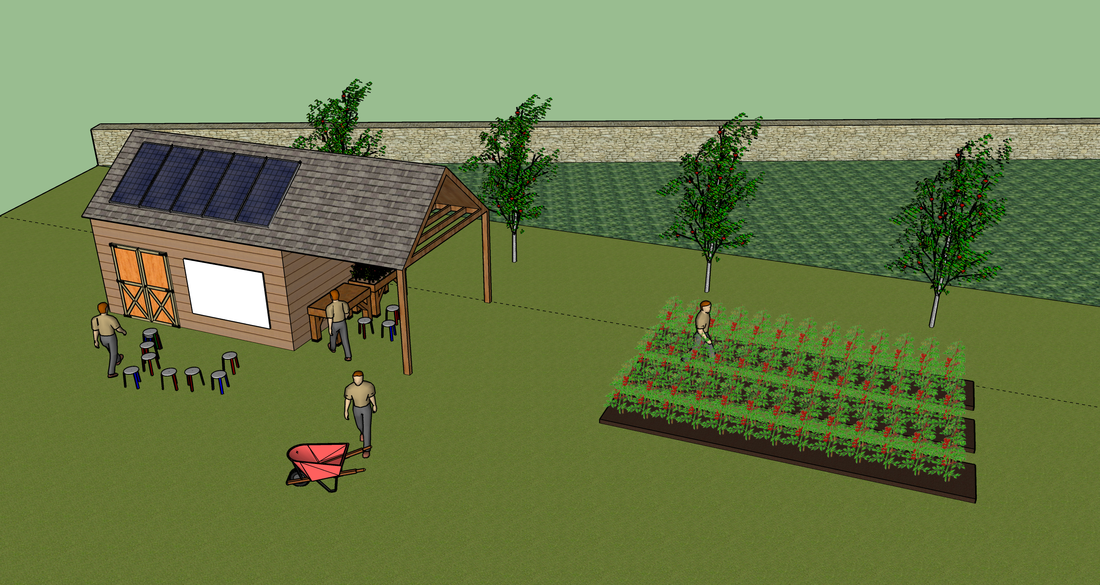

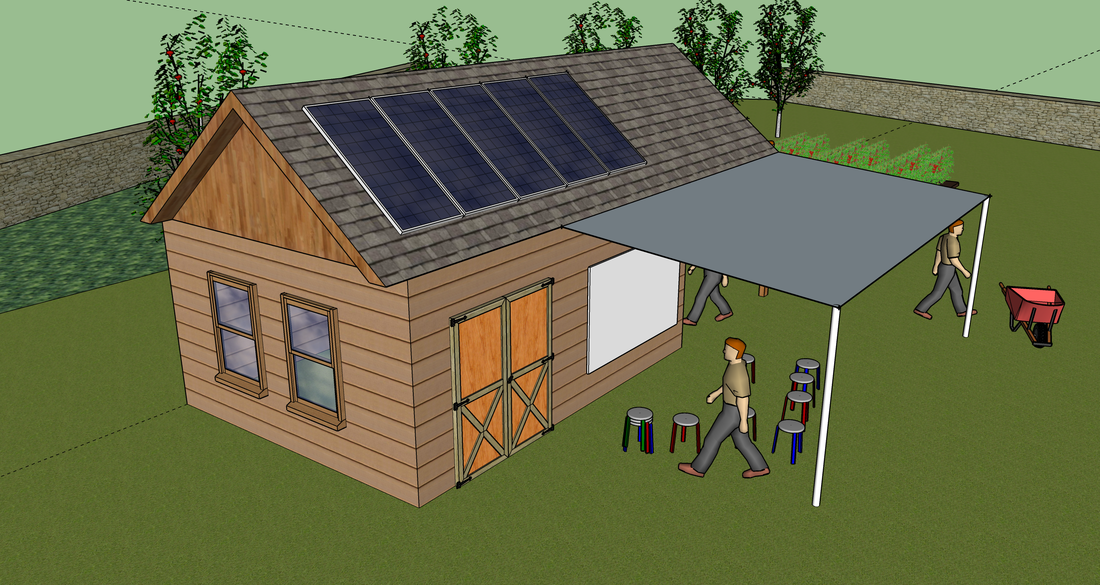

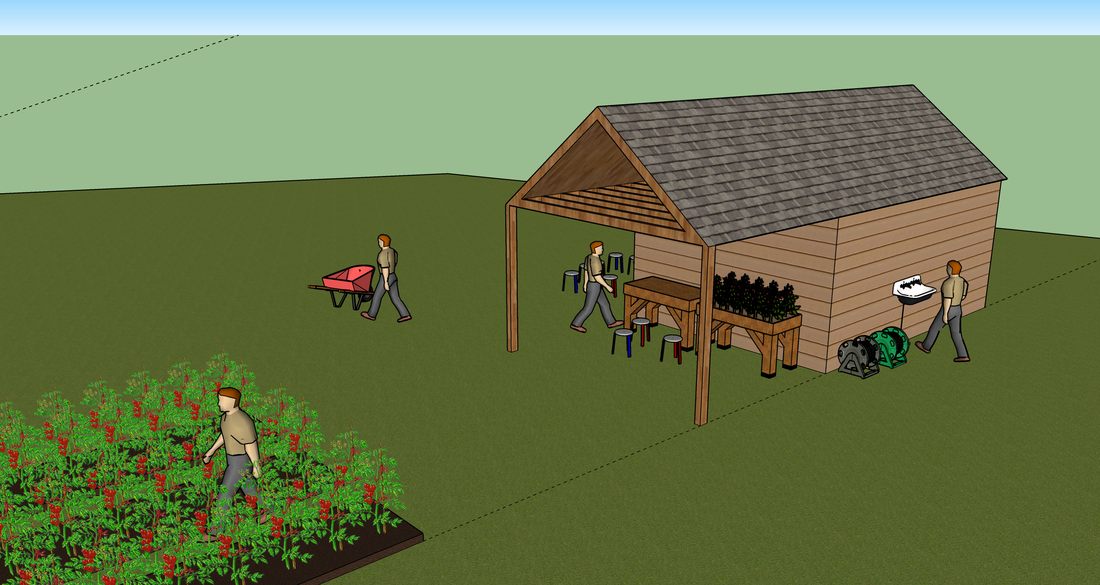

The two most useful and important guides that I discovered were the Makerspace Playbook, created by MakerEd and distributed by Maker Media, the publisher of Make: magazine, and the beautiful book Make Space: How to Set the Stage for Creative Collaboration by Scott Doorley and Scott Witthof, reflecting on their experience from Stanford’s d.School. Both resources delve deeply into the philosophy and goals of collaborative making spaces, and the ideas that they suggest for developing a space broadened and shaped my thinking hugely. Make Space in particular offers adaptable designs for handmade furniture, tools, and space definers, with the theory that a space full of locally-created useful objects sets the tone for ownership of a space and a DIY mentality. It also offers a wealth of thoughtful “Insights” for using a space, such as “Patina gives permission” (Doorley & Witthof, 202), one of my favorites. My thinking and designs evolved as the proposed spaces changed, and as the ideas morphed from a “grassroots” effort into a full school-sponsored initiative. The preliminary designs were for a dark, windowless space in the science building basement - an underutilized space that seemed like the easiest target for a grassroots takeover. Windowless and interrupted by a cinder block elevator shaft, the space was less than ideal, but at the time I wasn’t optimistic about the chances of the school committing higher-value space and resources to the proposal. As conversations “above my head” evolved, it became possible that another space might be available: the somewhat ignored and abused student center space. I adapted my designs to that larger and brighter space. In hindsight, that design was somewhat rigid - and would not have been very adaptable. That was the design, however, that was formally submitted along with a lengthy proposal to our administration. The proposal was approved, but with a caveat - the student center space would be converted to a new choral/lecture room, and the STEAM space would be located down the hall in what was at the time the weight room. What felt like a setback at the time may actually have been a blessing in disguise. My exploration of other spaces and resources continued, and my final proposal for the weight room space was substantially better in a number of ways than the design I had submitted in the initial proposal. It was more flexible and adaptable, had more built-in project storage space, and the design more carefully considered the various experiences that we wanted to offer the students. While the school hired architects and designers for the final design, my weight room design is fairly close to what was actually built. (See more renderings accompanied by some of my favorite Make Space quotes here.) As one would expect, the professional designers were able to add insights and experiences that I did not have, and raised the bar in several key ways. The most valuable adaptation? Glass. Rather than open “soft” separation between the office space, collaborative work space, and main classroom space, they designed closed but visible spaces with walls of glass. They also created an incredible glass entry wall, that gives passersby a “showcase” view of the space. I’ve lived in this space for 4 years now, and have loved the opportunities that it affords. It is a highly attractive and incredibly capable space, both for teachers and students. Since my primary classroom design dreams were largely fulfilled several years ago, I have been turning my attention to a satellite “classroom.” Our school is fortunate to have quite a bit of pastoral property. As our world continues to struggle with climate change, the stewardship of our planet, health and wellness, issues of food justice, questions surrounding GMO food, and increasing amounts of screen time, often at the cost of outdoor, natural time, it seems to me that an interactive outdoor STEAM learning space would provide incredible opportunities for our students. While I’ve put in some time over the past two years to consider what the programmatic elements might look like, I’ve recently been motivated to consider experiential design of spaces for learning once again. I updated my SketchUp license, and put some thoughts down in 3D space: The Third Teacher+ published a list called the 79 Ways You Can Use Design to Transform Teaching + Learning. While TTT+ generally focuses on the redesign of traditional (indoor) spaces, several of their list items stood out to me as equally relevant to outdoor spaces. Ideas such as, “Let the sunshine in, “Bring the outside in,” “Promote healthy play,” “Naturalize play spaces,” “Let your grassroots show,” “Roll up your sleeves,” “Get eco-educated,” “Highlight the site,” “Slow the pace,” “Define the learning landscape,” and “Put theory into practice.”

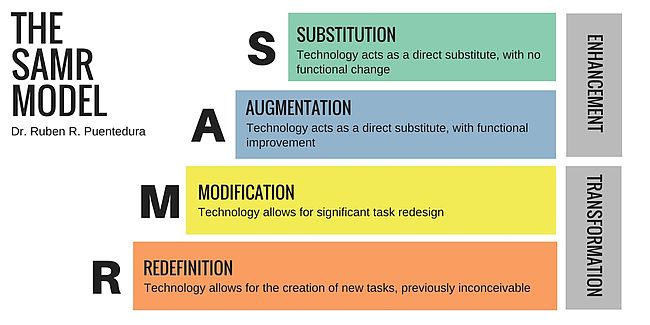

I imagine this learning space could be used across the curriculum - both integrating into existing courses and opening up possibilities for new courses and extracurricular learning. (See some of my curricular/co-curricular/extra-curricular thoughts here.) Spaces have the ability to expand rather than constrain thinking. Traditional “desks in a box” classrooms seem to dull, if not limit the imagination. Bringing learning outdoors might just be the thing we need. Over the past several years, virtual and augmented reality technologies have pushed their way from the periphery of nerdom closer to the mainstream. As the hardware has become more affordable, and software options expand, some educators are starting to explore whether or not these technologies may have a role in education. With my classmates in the MAET program at Michigan State, I explored several new learning spaces in the MSU Main Library, and was particularly intrigued by the VR Lab and the “360” - an circular continuous image projection space. To lay my biases plain, I entered the spaces with an inherent skepticism. While I am a strong proponent of most technology when used intentionally and creatively, I fear that the “iWorld” that we are creating is spreading loneliness and isolation. A VR headset device that physically and mentally shut out the “natural reality” world gives me pause. While it is clear that these immersive technologies are in their infancies, certain applications that we previewed started to break down my predispositions. We explored faraway places with Google Expeditions, saw beautiful and evocative line art animations of a children’s story, and watched a team of designers “walk through” and refine the digital design of an interior space. As cool and engaging as it is to consume content in these ways, the evolution of technology has a way of quickly raising the bar along with it. The excitement and shine of new gadgets gizmos wears off as soon as the next “generation” is released. If we are to explore this technology in education, how can we ensure that we’re not investing time and resources in a fancy tool, simply to consume content in slightly different way that is “cool” until the next thing comes along? Ruben Puentedura is well known as the creator of the SAMR model of technology integration in education (Puentedura, 2006). His model gives us a method of evaluating whether an integrated technology is simply enhancing the experience, or whether it is truly transformational for the learning space. As trendy technologies come and go, it is easy to get stuck in the substitution and augmentation phases. We consume new styles of content on different kinds of devices, but we don’t stretch far beyond the same basic things we’ve always done. By Lefflerd [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons The TPACK model suggests that in order to develop high-level technology integrations (such as Puentedura’s modification and redefinition phases), we need to develop expertise and experiences with our content area, with pedagogical methods, and with different technology tools (Koehler & Mishra, 2008). Expert-level knowledge in certain areas gives people the ability to make connections with little mental effort - often simply noticing relationships or ideas that are otherwise invisible to novices (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999). This type of sophisticated knowledge, along with the confidence to risk failure by trying something new, can result in a high likelihood of what we might call inventive, innovative, or creative solutions. By resisting the exploration of virtual and augmented reality, I’ve all but assured that I will never discover new and innovative ways to teach my students using this technology. If we as educators resist the “deep dive” into new technologies, and are satisfied to teach with technology of which we only have a cursory knowledge, we are guaranteed the same fate. We preach the gospel of creativity to our 21st century students, but we need to continue to develop our own growth mindset and our creative confidence in order to lead the way. Of their students at Stanford’s “d.school”, David and Tom Kelly (2012) write, “...we’ve learned that our job isn’t to teach them creativity. It’s to help them rediscover their creative confidence—the natural ability to come up with new ideas and the courage to try them out. We do this by giving them strategies to get past four fears that hold most of us back: fear of the messy unknown, fear of being judged, fear of the first step, and fear of losing control” (p.115). If we want to guide our students beyond content consumption with new technology to more meaningful content creation and exploration, we need to get beyond our own fears and predispositions. We can be skeptical followers, waiting for someone to “prove it” for us, or we can be the leaders that are making the important connections between technology, content, and pedagogy that can transform and redefine our fields. In the cliche but wise words of M. Gandhi, “If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. ... We need not wait to see what others do.” References: Herring, M. (Ed.), Koehler, M. (Ed.), Mishra, P. (Ed.), Published by The AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.). (2008). Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) for Educators. New York: Routledge. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press. Kelley, Tom & Kelley, David. (2012). Reclaim Your Creative Confidence. Harvard business review. 90. 115-8, 135. Puentedura, R. R. (2006, November 28). Transformation, technology, and education in the state of Maine [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2006_11.html |

AuthorNate is the Director of Technology at the Roxbury Latin School Archives

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed