|

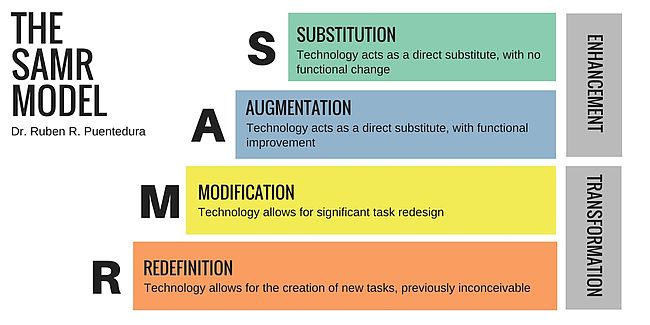

Over the past several years, virtual and augmented reality technologies have pushed their way from the periphery of nerdom closer to the mainstream. As the hardware has become more affordable, and software options expand, some educators are starting to explore whether or not these technologies may have a role in education. With my classmates in the MAET program at Michigan State, I explored several new learning spaces in the MSU Main Library, and was particularly intrigued by the VR Lab and the “360” - an circular continuous image projection space. To lay my biases plain, I entered the spaces with an inherent skepticism. While I am a strong proponent of most technology when used intentionally and creatively, I fear that the “iWorld” that we are creating is spreading loneliness and isolation. A VR headset device that physically and mentally shut out the “natural reality” world gives me pause. While it is clear that these immersive technologies are in their infancies, certain applications that we previewed started to break down my predispositions. We explored faraway places with Google Expeditions, saw beautiful and evocative line art animations of a children’s story, and watched a team of designers “walk through” and refine the digital design of an interior space. As cool and engaging as it is to consume content in these ways, the evolution of technology has a way of quickly raising the bar along with it. The excitement and shine of new gadgets gizmos wears off as soon as the next “generation” is released. If we are to explore this technology in education, how can we ensure that we’re not investing time and resources in a fancy tool, simply to consume content in slightly different way that is “cool” until the next thing comes along? Ruben Puentedura is well known as the creator of the SAMR model of technology integration in education (Puentedura, 2006). His model gives us a method of evaluating whether an integrated technology is simply enhancing the experience, or whether it is truly transformational for the learning space. As trendy technologies come and go, it is easy to get stuck in the substitution and augmentation phases. We consume new styles of content on different kinds of devices, but we don’t stretch far beyond the same basic things we’ve always done. By Lefflerd [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons The TPACK model suggests that in order to develop high-level technology integrations (such as Puentedura’s modification and redefinition phases), we need to develop expertise and experiences with our content area, with pedagogical methods, and with different technology tools (Koehler & Mishra, 2008). Expert-level knowledge in certain areas gives people the ability to make connections with little mental effort - often simply noticing relationships or ideas that are otherwise invisible to novices (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999). This type of sophisticated knowledge, along with the confidence to risk failure by trying something new, can result in a high likelihood of what we might call inventive, innovative, or creative solutions. By resisting the exploration of virtual and augmented reality, I’ve all but assured that I will never discover new and innovative ways to teach my students using this technology. If we as educators resist the “deep dive” into new technologies, and are satisfied to teach with technology of which we only have a cursory knowledge, we are guaranteed the same fate. We preach the gospel of creativity to our 21st century students, but we need to continue to develop our own growth mindset and our creative confidence in order to lead the way. Of their students at Stanford’s “d.school”, David and Tom Kelly (2012) write, “...we’ve learned that our job isn’t to teach them creativity. It’s to help them rediscover their creative confidence—the natural ability to come up with new ideas and the courage to try them out. We do this by giving them strategies to get past four fears that hold most of us back: fear of the messy unknown, fear of being judged, fear of the first step, and fear of losing control” (p.115). If we want to guide our students beyond content consumption with new technology to more meaningful content creation and exploration, we need to get beyond our own fears and predispositions. We can be skeptical followers, waiting for someone to “prove it” for us, or we can be the leaders that are making the important connections between technology, content, and pedagogy that can transform and redefine our fields. In the cliche but wise words of M. Gandhi, “If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. ... We need not wait to see what others do.” References: Herring, M. (Ed.), Koehler, M. (Ed.), Mishra, P. (Ed.), Published by The AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.). (2008). Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) for Educators. New York: Routledge. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press. Kelley, Tom & Kelley, David. (2012). Reclaim Your Creative Confidence. Harvard business review. 90. 115-8, 135. Puentedura, R. R. (2006, November 28). Transformation, technology, and education in the state of Maine [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2006_11.html

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorNate is the Director of Technology at the Roxbury Latin School Archives

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed