|

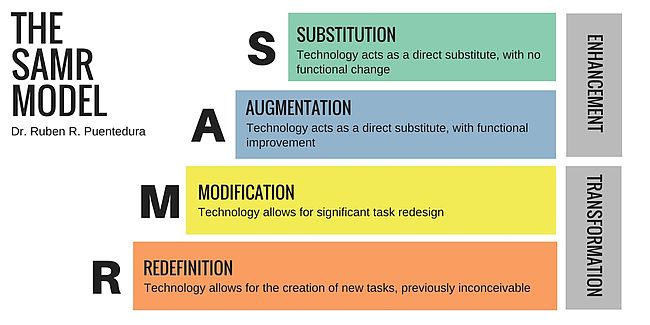

Over the past several years, virtual and augmented reality technologies have pushed their way from the periphery of nerdom closer to the mainstream. As the hardware has become more affordable, and software options expand, some educators are starting to explore whether or not these technologies may have a role in education. With my classmates in the MAET program at Michigan State, I explored several new learning spaces in the MSU Main Library, and was particularly intrigued by the VR Lab and the “360” - an circular continuous image projection space. To lay my biases plain, I entered the spaces with an inherent skepticism. While I am a strong proponent of most technology when used intentionally and creatively, I fear that the “iWorld” that we are creating is spreading loneliness and isolation. A VR headset device that physically and mentally shut out the “natural reality” world gives me pause. While it is clear that these immersive technologies are in their infancies, certain applications that we previewed started to break down my predispositions. We explored faraway places with Google Expeditions, saw beautiful and evocative line art animations of a children’s story, and watched a team of designers “walk through” and refine the digital design of an interior space. As cool and engaging as it is to consume content in these ways, the evolution of technology has a way of quickly raising the bar along with it. The excitement and shine of new gadgets gizmos wears off as soon as the next “generation” is released. If we are to explore this technology in education, how can we ensure that we’re not investing time and resources in a fancy tool, simply to consume content in slightly different way that is “cool” until the next thing comes along? Ruben Puentedura is well known as the creator of the SAMR model of technology integration in education (Puentedura, 2006). His model gives us a method of evaluating whether an integrated technology is simply enhancing the experience, or whether it is truly transformational for the learning space. As trendy technologies come and go, it is easy to get stuck in the substitution and augmentation phases. We consume new styles of content on different kinds of devices, but we don’t stretch far beyond the same basic things we’ve always done. By Lefflerd [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], from Wikimedia Commons The TPACK model suggests that in order to develop high-level technology integrations (such as Puentedura’s modification and redefinition phases), we need to develop expertise and experiences with our content area, with pedagogical methods, and with different technology tools (Koehler & Mishra, 2008). Expert-level knowledge in certain areas gives people the ability to make connections with little mental effort - often simply noticing relationships or ideas that are otherwise invisible to novices (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999). This type of sophisticated knowledge, along with the confidence to risk failure by trying something new, can result in a high likelihood of what we might call inventive, innovative, or creative solutions. By resisting the exploration of virtual and augmented reality, I’ve all but assured that I will never discover new and innovative ways to teach my students using this technology. If we as educators resist the “deep dive” into new technologies, and are satisfied to teach with technology of which we only have a cursory knowledge, we are guaranteed the same fate. We preach the gospel of creativity to our 21st century students, but we need to continue to develop our own growth mindset and our creative confidence in order to lead the way. Of their students at Stanford’s “d.school”, David and Tom Kelly (2012) write, “...we’ve learned that our job isn’t to teach them creativity. It’s to help them rediscover their creative confidence—the natural ability to come up with new ideas and the courage to try them out. We do this by giving them strategies to get past four fears that hold most of us back: fear of the messy unknown, fear of being judged, fear of the first step, and fear of losing control” (p.115). If we want to guide our students beyond content consumption with new technology to more meaningful content creation and exploration, we need to get beyond our own fears and predispositions. We can be skeptical followers, waiting for someone to “prove it” for us, or we can be the leaders that are making the important connections between technology, content, and pedagogy that can transform and redefine our fields. In the cliche but wise words of M. Gandhi, “If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. ... We need not wait to see what others do.” References: Herring, M. (Ed.), Koehler, M. (Ed.), Mishra, P. (Ed.), Published by The AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.). (2008). Handbook of Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPCK) for Educators. New York: Routledge. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press. Kelley, Tom & Kelley, David. (2012). Reclaim Your Creative Confidence. Harvard business review. 90. 115-8, 135. Puentedura, R. R. (2006, November 28). Transformation, technology, and education in the state of Maine [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2006_11.html

0 Comments

I can't claim to have a Nonna, or even any substantial Italian heritage, but I do have an appreciation for a "just right" tomato sauce over fresh, perfectly al-dente pasta. My wife and I go through so much pre-made pasta sauce and salsa each year, that this past Spring, I embarked on a tomato-growing adventure. The picture above captures about a dozen tomatillo plants, nearly 50 tomato plants (half "Amish Paste" and half "Cherokee Purple"), and a handful of hot pepper plants, on a piece of land graciously lent to me by my school. The idea is that the tomatoes will yield an enormous crop - plenty for all the fresh eating we can imagine, and plenty left over for all the cooking and preserving that we have the time or energy to take on.

The potential hitch in the plans is that I've never grown more than a couple tomato plants in our city-sized side yard, and have never actually made tomato sauce or salsa from fresh tomatoes. I'll take on the challenge of learning how to cook and can (mason-jar) delicious pasta sauce for my "Networked Learning Project" - a part of my first year experience in Michigan State University's MAET graduate program. I'll avoid online recipe books (traditional media, just stuck online), and instead focus on the strong opinions and unique experiences of YouTube amateurs and online forum contributors, who I'm sure each believe wholeheartedly that their technique is the one-and-only "best ever." Stay tuned for the inevitable trials and tribulations of Nate's Sauce, v1.0. As the parent of a one-year old, learning is not simply an abstract concept to be studied, but rather a front-and-center daily experience. The world is a brand new place for this little human, and his spongy infant brain is absorbing information constantly, resulting in daily changes and developments. As human beings, we are all engaged in a constant learning exercise. While we may not change as dramatically as my son does from one day to the next, everything that we experience contributes to the bank of information and experiences that we call knowledge.

My son knows what a raisin is. He likes raisins. He has learned what a raisin is because I put them on his highchair tray and I tell him that they are raisins. His understanding of what a raisin is, however, is different than mine, and my understanding of raisins is certainly different than that of the fine folks at Sun-MaidⓇ. Learning facts can take place in isolated moments, but understanding evolves over time as we learn new information and reevaluate our former understanding; a process known as conceptual change (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 1999). Thus far, most of my son’s learning has been driven by relatively passive observation, with occasional suggestion from his parents. As he gets older, however, and particularly when he goes to school, he will be engaged in a more formal style of learning. Rather than simply taking in his world and making associations, his teachers will determine certain knowledge and skills that they intend for him to learn. If we (as educators) aim to teach, that is, attempt to induce learning in another - we must understand how people learn, and develop a deeper awareness of the underlying mechanisms of learning, understanding, and conceptual change. In the pursuit of effective teaching, committed educators endeavor to find pedagogical approaches that fit within their cultures and contexts, and maximize the likelihood of meaningfully engaging their students. The growing maker movement is one such approach. Halverson and Sheridan (2014) have explored the maker movement in education, and discuss the research opportunities that it affords. They applaud several related research ventures, saying, “We are encouraged that these pieces begin the research conversation on the maker movement with subtlety, rather than asking whether making is simply “good” or “bad” for learners and instructional environments” (p. 503). As with nearly any teaching method, making can be a successful strategy, but cannot be broadly categorized as a binary positive or negative approach. A pedagogical “silver bullet” would be convenient, but it is simply not practical. Teaching toward learning, understanding, and contextual change typically requires a carefully choreographed combination of teaching methods and styles, which need to be adapted and and often reinvented for different contexts. According to Bransford, Brown, and Cocking (1999), “Asking which teaching technique is best is analogous to asking which tool is best— a hammer, a screwdriver, a knife, or pliers. In teaching as in carpentry, the selection of tools depends on the task at hand and the materials one is working with” (p. 22). Technological tools can play a prominent role in the 21st century toolbox, but the inherent affordances and constraints of the technology must be considered thoughtfully (Koehler & Mishra, 2008). In a program of study that focuses on educational technologies and their integration with content and pedagogy, it is crucial study how people learn. Mishra and Koehler (2009) state that, “Teaching is not a process of picking up a few instructional techniques and applying them. It emerges from thinking deeply about the nature of a discipline in conjunction with strategies for helping students learn that discipline over time” (p. 15). Understanding how students learn is an obvious prerequisite for helping them to learn. If we aim to improve learning outcomes with technology, we must be continuously thoughtful about the ways in which people learn, and how technology can bring students closer to deep learning and understanding. References: Halverson, Erica & Sheridan, Kimberly. (2014). The Maker Movement in Education. Harvard Educational Review. 84. 495-504. 10.17763/haer.84.4.34j1g68140382063. Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC, US: National Academy Press. Herring, M. (Ed.), Koehler, M. (Ed.), Mishra, P. (Ed.), Published by The AACTE Committee on Koehler, M.J., & Mishra, P. (2008). Introducing TPCK. AACTE Committee on Innovation and Technology (Ed.), The handbook of technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPCK) for educators (pp. 3-29). American Association of Colleges of Teacher Education and Rougledge, NY, New York. Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2009, May). Too Cool for School? No Way! Learning & Leading with Technology, (36)7. 14-18. |

AuthorNate is the Director of Technology at the Roxbury Latin School Archives

January 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed